by Noor Hellmann

The signpost to Sobibor camp is inconspicuous; you could easily miss the turn. The bus leaves the straight two-lane road and bumps along the poorly maintained asphalt, through a marshy area with pine trees, birches, and other deciduous trees now in autumn colors. Occasionally, the forest gives way to open fields – the surroundings are more beautiful than I had imagined.

This memory goes back to 2015 when I first joined a memorial trip organized by the Sobibor Foundation. We stayed overnight in Lublin, in eastern Poland. Now, nine years later, I am making such a group trip again, this time with three generations of my family. I have a déjà vu as we check into the same hotel, on the edge of the former ghetto in the city center. Some buildings in the old center have bricked-up windows with large black-and-white portraits of former residents. From my hotel room, I have a view of a facade with a photo of a woman in a white dress, as if she is sitting on her balcony.

Quiet Corner

In the pouring rain, we leave for Sobibor the next morning. After two hours, there is a stop in Wlodawa to visit the baroque synagogue, which now serves as a Jewish museum. Little remains of the rich Jewish life in the town before the war. Only about a hundred Jewish residents survived the Holocaust.

From Wlodawa, it is another sixteen kilometers to Sobibor. We approach the border with Ukraine and Belarus; the war in Ukraine seems an unreal idea in this quiet corner. Much further away, bombs, shells, and rockets are also raining down: I feel that the escalated conflict between Israel and Hamas accompanies our journey like a dark cloud, although remembrance must take precedence. On the way, I read “Letter in the Night. Thoughts on Israel and Gaza” by Chaja Polak. The author lost her father in the war, and her late husband almost his entire family. In her beautiful essay, she expresses her confusion and dismay over the hopeless struggle between Israelis and Palestinians. She analyzes with a nuanced view and does not shy away from painful questions. Yes, I think as I read her, yes, that’s how I see it too.

Nineteen Trains

My first visit to Sobibor was an emotional experience. I had read about the camp and knew television images of the railway, the platform, and the rusted station sign Sobibor. But walking around there was something else entirely. Here, my grandfather, 39 years old, had taken his last steps. From the platform, it was a few hundred meters to the gas chambers. With 1251 others, he was deported on the fifth train from Westerbork to Sobibor, which reached its destination on April 2, 1943, near the village of Sobibor.

In total, nineteen trains arrived from Westerbork. They transported over 34,000 people, a third of the total number of Jews killed from the Netherlands. The complete name lists are included in “Extermination Camp Sobibor,” the standard work by survivor Jules Schelvis. Sobibor, in operation from May 1942 to October 1943, was an efficient extermination industry that was an important link for the Nazis in “solving the Jewish question.” About 170,000 Jews were killed there immediately upon arrival; it could be significantly more, estimates vary. These are the cold numbers, rounded for convenience, as if each life does not count.

Individual Stories

That my two daughters are coming along this time gives the trip extra meaning. They are in their twenties; the war and the death of their betrayed and deported great-grandfather are far behind them, but emotionally, the distance is not so great. They feel connected to the story of their grandfather Paul, who, according to the Nazis, had no right to exist. As a seven-year-old boy, he suddenly had a star sewn onto his clothes. He had no idea what it meant to be Jewish; nothing was done at home about the holidays and traditions. Not long after, the star was torn off again when his parents and he had to go into hiding, all three in different places. The last time he saw his father was on the garden path of his hiding place, where they said goodbye to each other.

It is individual histories that bring the past close. During our trip, we not only visit the impressive Polin Museum in Warsaw, which pays extensive attention to the Holocaust that cost three million Polish Jews their lives, but we also go to the Jewish Historical Institute in the capital. The institute possesses the clandestine archive “Oneg Shabbat,” a kind of testament of the ghetto residents in Warsaw. Historian Emanuel Ringelblum was one of the initiators who called on his fellow residents to record as much as possible on paper. The collected testimonies and documents were hidden in cans and milk churns. “What we could not shout to the world, we buried underground.” After the war, a wealth

of information was found – one of the used milk churns stands rusty and battered on display.

Uprising

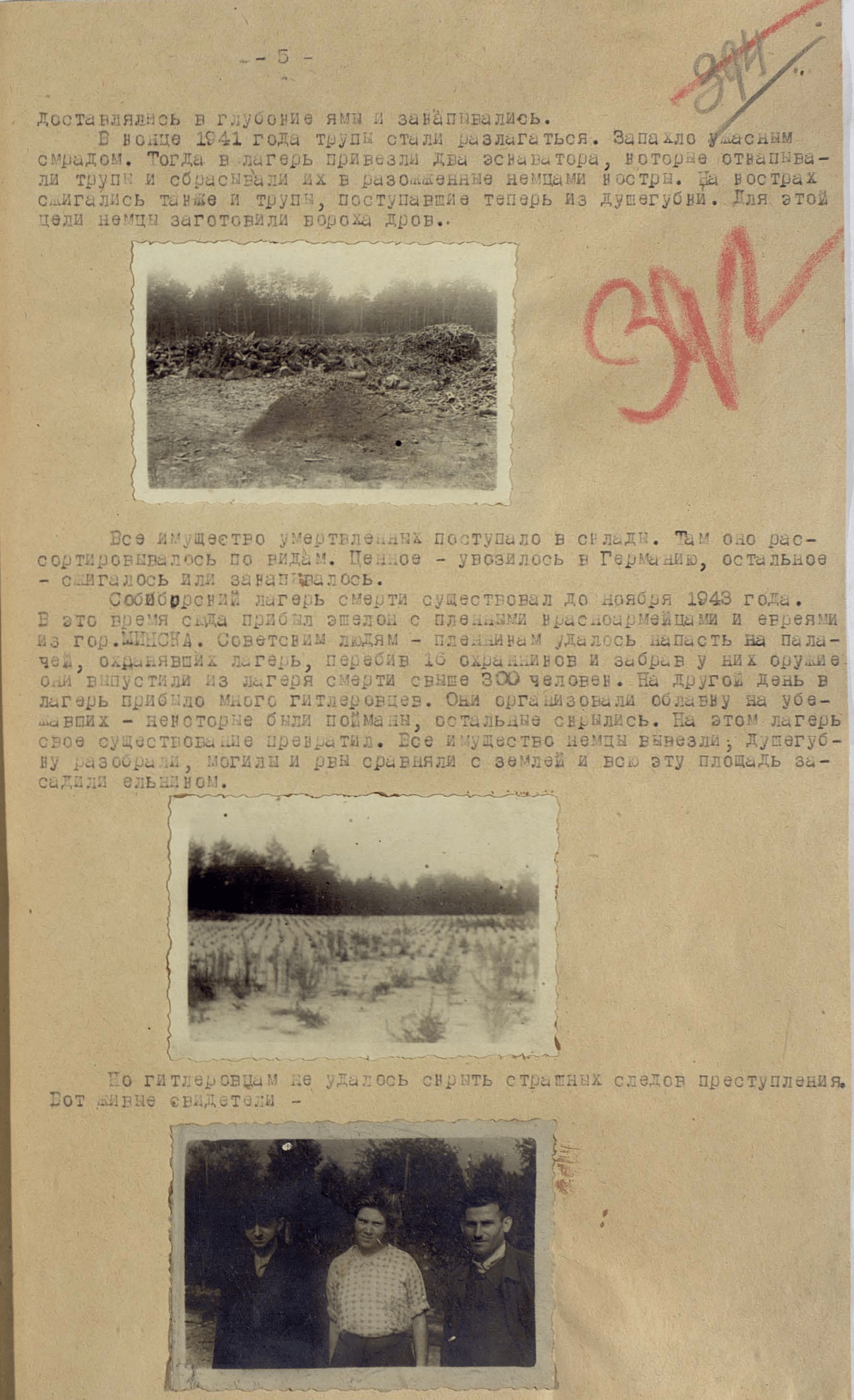

For a long time after the war, little was known about Sobibor; it seemed a kind of blind spot in the collective memory. Those who knew the way there found a desolate place in a dark forest, where seemingly little remained that referred to the mass murder that had taken place there. Imagination had to do the work. Already in the middle of the war, the visible traces were erased. The reason was the well-prepared uprising on October 14, 1943. About three hundred prisoners managed to escape – most of whom unfortunately did not survive the flight. Twelve SS men and several Ukrainian guards were killed. For the SS headquarters in Berlin, the breakout was a severe setback, and it was decided to immediately raze the camp to the ground. Where the barracks stood, the Germans planted young trees.

In 2007, a thorough reconstruction of the site began. An international team of archaeologists discovered the foundations of the gas chambers and over the years unearthed many lost and abandoned personal belongings. It became clear that the Himmelfahrtstrasse, the route to the gas chambers, was located elsewhere than previously assumed. The project was completed at the end of 2023.

Eyewitness Accounts

When our bus arrives at the empty parking lot, the appearance of the camp has changed, but the platform looks just as it did before the renovation. Weeds grow tall between the concrete slabs. The track is used for timber transport in the summer, and passenger trains also run. A current timetable at the small station across the way shows that the train between Wlodawa and Chelm passes four times a day.

When our bus arrives at the empty parking lot, the appearance of the camp has changed, but the platform looks just as it did before the renovation. Weeds grow tall between the concrete slabs. The track is used for timber transport in the summer, and passenger trains also run. A current timetable at the small station across the way shows that the train between Wlodawa and Chelm passes four times a day.

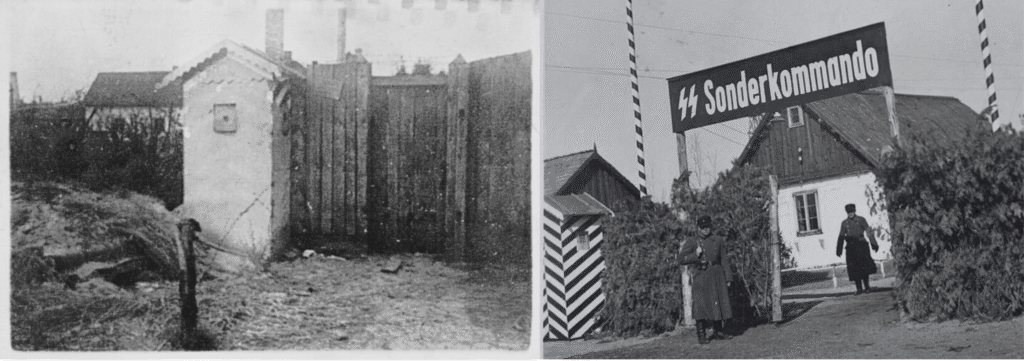

The rain has turned into a light drizzle as we all stand on the platform. Petra van den Boomgaard and Maarten Eddes, who organized this trip, introduce our visit with an informative story about the 1943 uprising. Although the Nazis wanted Sobibor to remain a “top secret,” according to writer Jules Schelvis, much has been reconstructed afterward. Photos from the estate of SS camp commander Johann Niemann, which surfaced a few years ago and were published in the book “Fotos aus Sobibor,” provide a picture of the camp. The eyewitness accounts of the uprising are also very important. My daughters and the other four young people in our group take turns reading quotes.

Meanwhile, a stiff, old dog shuffles out of a garden opposite the platform. It is the garden of a green wooden house with a red roof. It once served as the camp commander’s quarters; the Germans left it standing when they hurriedly departed. This house and the two adjacent houses, right next to the campgrounds, are inhabited. I was surprised by this the last time as well.

Journalist Rosanne Kropman spoke for her 2023 book “The Darkest Dark, a History of Sobibor” with Jerzy Zielinski, the resident of the green house. His wife was born there after the war. Kropman writes: “It’s not really nice to live here, he thinks. The woodwork from 1923 needs a lot of maintenance, the house is not insulated and is heated with a wood stove. But living in a guilty landscape does not bother him. (…). The track over which the trains were shunted into the camp ran a few meters from Zielinski’s front door; his backyard overlooked Lager I during the war, where the forced laborers lived. It was within the tightly guarded double fences. ‘What does it matter,’ says Jerzy Zielinski. ‘The commander just lived here, just like I live here now.'”

Naming Names

Since the renovation, Sobibor has a new museum and memorial center. The large building is the first thing you see upon arrival. Inside, excavated artifacts are displayed. Nail scissors, combs, plates, and cutlery – all sorts of items that the prisoners thought they needed when they were misled into thinking they were going to a “labor camp.” There is a lot of information in text and images, including from Niemann’s album, such as a photo of some cheerful SS men and their wives, sitting outside at a table. According to the caption, the man in the middle is Erich Bauer, the “gas master” of Sobibor. Paul Celan’s chilling poem “Death Fugue” comes to mind: suddenly I understand the line “death is a master from Germany.”

Behind the museum, the campgrounds stretch out. Initially, you could see up to the edge of the forest; now there is a high concrete wall around it, suggesting that we are cut off from the world. Within the enclosure, at the edge of a gravel plain, we hold a memorial with the group under a gray cloud cover. Inaccessible in the distance lies the ash mound, covered with gravel. A final resting place for the dead. The relatives name their murdered family members, sometimes it is a long list. I am moved when my father steps forward and says: “Bernhard Hellmann, my lost father. I miss him, and it only gets worse with the years.” Words that, in their simplicity, hit the core. A crow caws as we stand silent for two minutes, the treetops rustle. Are we standing here in a “guilty landscape” where you can hear the souls of the deceased whisper?

Great Spotted Woodpecker

In the memorial avenue, relatives have placed memorial stones, varying in size and provided with new silver-colored nameplates. After some searching, we find the stone for Bernhard. We place pebbles and light a candle in a plastic holder, a lid with holes protecting the flame from wind and rain. It feels as if we are finally standing at his grave after a long journey, tears prick our eyes. Then, nearby, a soft and regular tapping suddenly sounds. It turns out to be a great spotted woodpecker high in a pine tree, busily pecking at the trunk. My grandfather, who as a great animal lover studied animal behavior from a young age, would have observed him with interest.

When we return to the Netherlands after four days, we come from another world. A sense of solidarity has developed in the group. While we were served Jewish meals at long, beautifully set tables in the evenings, we listened to each other’s stories, surrounded by the shadows of the people who disappeared and never returned.

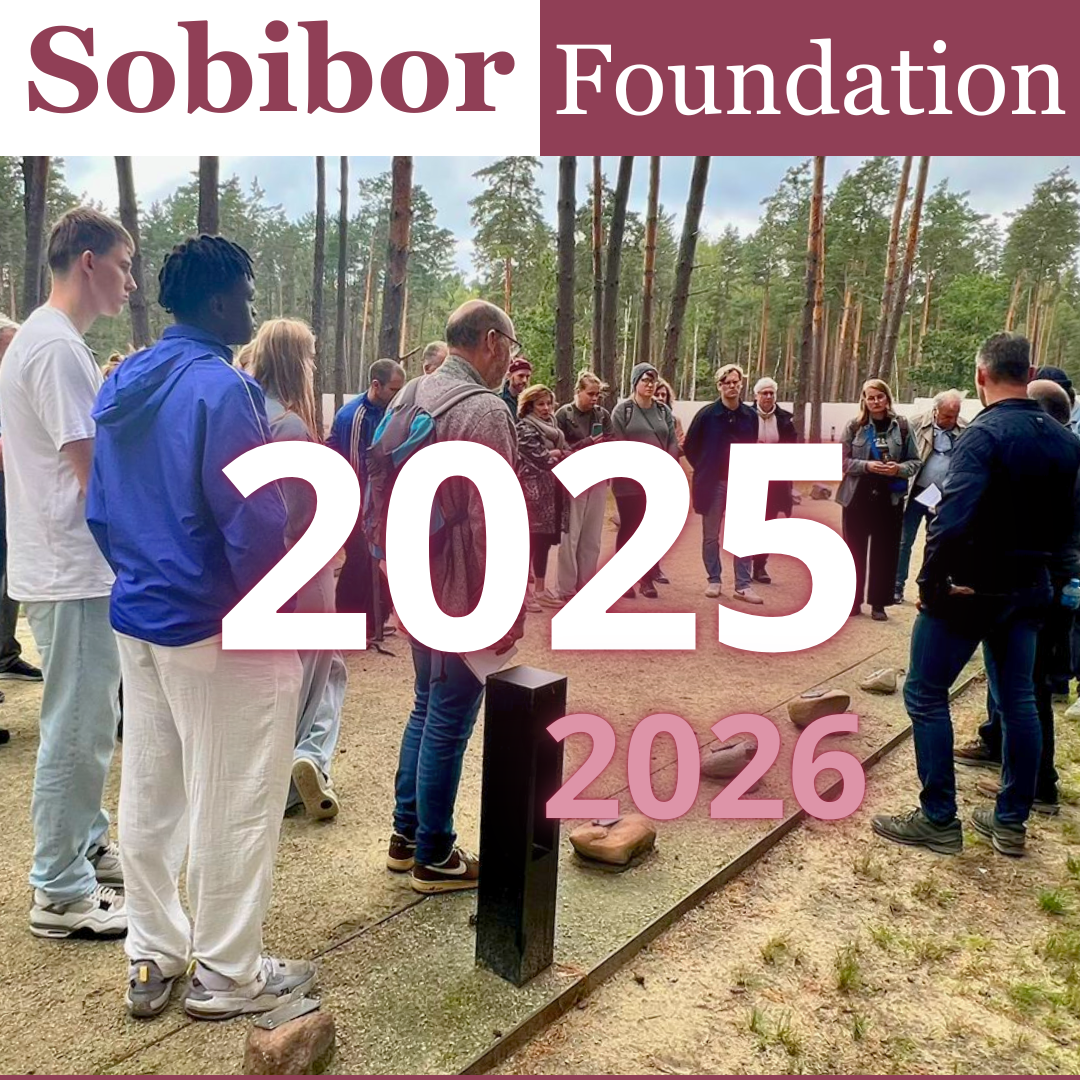

It seems like the year 2025 has flown by even faster than previous years! The present quickly becomes the past. What I feel most strongly is that we must continue to take time to commemorate the past in a meaningful way; how do we place Sobibor in the perspective of the here and now? The world is on fire, and adversarial thinking has become the norm for many in public debate. That is a bitter pill for us at the Sobibor Foundation. While we strive to engage in dialogue by connecting past and present, it sometimes seems as though the past no longer matters. Fortunately, this past year the government launched the National Plan for Strengthening Holocaust Education, enabling all institutions and organizations involved to join forces. Let’s hope this keeps the conversation alive. The high school students who traveled with us to Sobibor for the first time this year showed us that they are more than capable of having that conversation; the question “What if I had been one of them…?” was asked often—not only in the context of victims, but also perpetrators and bystanders. This inspired us so much that in the new year we will once again dedicate our full energy to spreading our message: “Remember through information and education.”

It seems like the year 2025 has flown by even faster than previous years! The present quickly becomes the past. What I feel most strongly is that we must continue to take time to commemorate the past in a meaningful way; how do we place Sobibor in the perspective of the here and now? The world is on fire, and adversarial thinking has become the norm for many in public debate. That is a bitter pill for us at the Sobibor Foundation. While we strive to engage in dialogue by connecting past and present, it sometimes seems as though the past no longer matters. Fortunately, this past year the government launched the National Plan for Strengthening Holocaust Education, enabling all institutions and organizations involved to join forces. Let’s hope this keeps the conversation alive. The high school students who traveled with us to Sobibor for the first time this year showed us that they are more than capable of having that conversation; the question “What if I had been one of them…?” was asked often—not only in the context of victims, but also perpetrators and bystanders. This inspired us so much that in the new year we will once again dedicate our full energy to spreading our message: “Remember through information and education.”

When our bus arrives at the empty parking lot, the appearance of the camp has changed, but the platform looks just as it did before the renovation. Weeds grow tall between the concrete slabs. The track is used for timber transport in the summer, and passenger trains also run. A current timetable at the small station across the way shows that the train between Wlodawa and Chelm passes four times a day.

When our bus arrives at the empty parking lot, the appearance of the camp has changed, but the platform looks just as it did before the renovation. Weeds grow tall between the concrete slabs. The track is used for timber transport in the summer, and passenger trains also run. A current timetable at the small station across the way shows that the train between Wlodawa and Chelm passes four times a day.

After the conversation led by Petra van den Boomgaard with Kropman and Schumacher, the question came up, “Was there a connection between the escape tunnel and the murder of the captain? Actually, the answer does not matter. What matters is that this afternoon knowledge will be shared about Dutchmen in the camp and the results of archaeological excavations. Also important are the young people taking an interest in people who kept hope under the most difficult circumstances. Kept hope for a better future until the very last moment. Hope to make the horrors of Sobibor known to the world. That is resistance.

After the conversation led by Petra van den Boomgaard with Kropman and Schumacher, the question came up, “Was there a connection between the escape tunnel and the murder of the captain? Actually, the answer does not matter. What matters is that this afternoon knowledge will be shared about Dutchmen in the camp and the results of archaeological excavations. Also important are the young people taking an interest in people who kept hope under the most difficult circumstances. Kept hope for a better future until the very last moment. Hope to make the horrors of Sobibor known to the world. That is resistance.

The Sobibor Foundation participated in an International Seminar Tour in Lublin and Region June 16-21, 2024: Unveiling ‘Aktion Reinhardt’: A Multiperspective Exploration. The seminar was organized by Brama Grodzka Gate-Teatr NN in Lublin.

The Sobibor Foundation participated in an International Seminar Tour in Lublin and Region June 16-21, 2024: Unveiling ‘Aktion Reinhardt’: A Multiperspective Exploration. The seminar was organized by Brama Grodzka Gate-Teatr NN in Lublin.

This past May, Laurens van Hofslot and Olivia Rice, students from University College Utrecht, participated in the commemorative trip. Their involvement was linked to their participation in the interview project of Stichting Sobibor. For this project, both have interviewed various survivors and descendants of the Holocaust. The main goal of this ongoing project is to document the wartime and life stories for families. As a culmination, Olivia and Laurens joined the commemorative trip to Sobíbor.

This past May, Laurens van Hofslot and Olivia Rice, students from University College Utrecht, participated in the commemorative trip. Their involvement was linked to their participation in the interview project of Stichting Sobibor. For this project, both have interviewed various survivors and descendants of the Holocaust. The main goal of this ongoing project is to document the wartime and life stories for families. As a culmination, Olivia and Laurens joined the commemorative trip to Sobíbor. In accordance with Jewish tradition, we also held a memorial ceremony at the ash mound, where people could name their family members. This moment was very emotional and left a deep impression. It was very powerful to see and hear that, despite everything, these families could be here to honor their relatives, despite the immense suffering inflicted upon their families. Olivia writes how the kind and friendly group made this moment of remembrance in Sobibor camp even more poignant. “I truly realized that day what the impact of the Holocaust really was. It is easy in the academic world to distance yourself from the tragedies and human rights violations you learn about. The commemoration left an impact that ensures I will never do this again.” Laurens also writes that as a student, you can sometimes easily fall into the trap of dealing with Holocaust information in an academic manner, but this commemoration made the stories of the Holocaust tangible for him in a new way. The stark contrast between the location of Sobíbor camp—a seemingly peaceful place in the middle of the forest, where the sun shines, and birds sing—and the atrocities that took place there was jarring.

In accordance with Jewish tradition, we also held a memorial ceremony at the ash mound, where people could name their family members. This moment was very emotional and left a deep impression. It was very powerful to see and hear that, despite everything, these families could be here to honor their relatives, despite the immense suffering inflicted upon their families. Olivia writes how the kind and friendly group made this moment of remembrance in Sobibor camp even more poignant. “I truly realized that day what the impact of the Holocaust really was. It is easy in the academic world to distance yourself from the tragedies and human rights violations you learn about. The commemoration left an impact that ensures I will never do this again.” Laurens also writes that as a student, you can sometimes easily fall into the trap of dealing with Holocaust information in an academic manner, but this commemoration made the stories of the Holocaust tangible for him in a new way. The stark contrast between the location of Sobíbor camp—a seemingly peaceful place in the middle of the forest, where the sun shines, and birds sing—and the atrocities that took place there was jarring.